Cycle of Continuous Improvement Ccsso 2017

February 2018 Volume III Issue II

Marcia Baldanza, the author of Professional Practices and a Just ASK Senior Consultant, lives in Arlington, Virginia. Until recently she worked for the School District of Palm Beach County, Florida, where she was an Area Director for School Reform and Accountability; prior to that she was Director of Federal and State Programs.

School Improvement…

What Matters Most?

Part II

Last month, I began the discussion of PSEL Standard 10: School Improvement. In this issue, I continue the discussion. There are so many aspects of continuous school improvement that deserve a deeper dive.

What is school improvement and why does it really matter? To answer, I am taken by the words of Nanci Schneider, school improvement practitioner from Oregon, "What it means ultimately is helping the most challenged students learn more quickly, because the results show the negative consequences of falling behind. It also means convincing teachers – many of whom were "A" students who loved school when they were kids – that, with the right supports, every last kid in their classroom is capable of learning. Even though learning might not come as easily to some kids as it did to their teachers, all students can and will learn when the right supports are in place, and all teachers can make this happen in 180+ days a year."

Schneider blogs that, "School improvement – increasing student learning- requires teachers to be as sharp as a scalpel, quick as a wink, smart as a whip, and responsive to every student, including those who are homeless, those who have learning challenges, those who already know the material, and those who fit into as many categories as there are students in the classroom. This is what needs to happen all day, every day, all year long."

The urgency of accelerating improvement for a child has life-long impact. We are called to this hard and uplifting work supported by the PSEL and guided by a culture of learning. Is it fast? No. Is it easy? No. Is it doable? Yes!

In this issue of Professional Practices , I dive into practices for using test data to improve teaching and learning, strategies for developing a focus of inquiry for classroom walkthroughs, involving students in improvement efforts, accelerating not remediating and more. This is an issue for sharing with school leadership teams and teacher leaders.

What Matters in Improving Schools?

The Data Smart Principal

Most schools around the country administer some sort of interim assessment that measures student progress towards standards mastery. From these tests, principals and teachers sit together to review and design interventions. District staffs look to see where to shift resources and strengthen curriculum and even attempt to predict end-of-the-year performance. Seem overwhelming? Relax! Take a deep breath and read on. I share three models or cycles of improvement in use today and that are making a difference for our students. What's important is that you choose one model and stick to it. Teach it to your teachers, model it in meetings, and reference it whenever you can. Make being data-smart part of your school culture.

There are so many data points to consider. Where do you start? How do you make time for the work? How do you build your faculty's ASK (attitude, skill, and knowledge) to interpret data sensibly? How do you build a culture on improvement, not blame? How do you maintain momentum in the face of all of the other demands at your school? I read those questions posed in a 2006 issue of the Harvard Education Letter, and more than a decade later, I still ask those questions. To be fair, we're light years from where we started and our data have become more sophisticated and varied in our collection and analysis.

What I learned while a principal, a district administrator, and now as a university professor, is that some sort of organizing framework built on collaborative structures is the way to be smart, confident, and skillful with data. The work of using data to improve instruction should be cyclical in nature and involves sequential steps organized into logical phases.

Harvard Data Wise Improvement Process

The Harvard Data Wise Improvement Process is an eight-step model that guides teams of educators from schools or systems in working collaboratively to improve teaching and learning through evidence-based analysis. The steps occur in three phases. The "Prepare" phase involves creating and maintaining a culture in which staff members can collaborate effectively and use data responsibly. In the "Inquire" phase, educators use a wide range of data sources, including test data, student work, and classroom observations, so that they can define a very specific problem of practice that they are committed to solving. In the "Act" phase, teams articulate how they will learn and employ high-leverage strategies to address their problem, and how they will assess the extent to which the plan improved outcomes they care about. After educators assess the effectiveness of their actions, they can both identify needed adjustments to their plan and determine the focus for the next cycle of collaborative inquiry.

The habits of mind that underlie the work include a shared commitment to action, assessment and adjustment; intentional collaboration; and a relentless focus on evidence. Learn more about this model at: https://datawise.gse.harvard.edu/

Deming's Total Quality Management Model

Plan – Do – Check – Act

Plan

Data Disaggregation

In this step administrators and teachers analyze the state standardized test data to identify students' and teachers' strengths and weaknesses. Focusing on specific student weaknesses, Teachers and administrators create a plan for student improvement. Looking at teacher weaknesses can help identify knowledge of skill deficits and target professional growth.

Timeline Development

Based on the students' strengths and weaknesses, teams build an instructional calendar. It is recommended that grade level focus on the same standard at the same time so that a trend analysis can be captured. The calendar should be flexible enough to allow for adjustments thus providing additional time for students to obtain mastery. The calendar should also clearly allocate time for assessment periods, enrichment, and tutorials.

Do

Check

Assessment

After teaching the targeted standard, teachers administer short on-going assessments that check for student understanding.

- The assessment should, at times, mimic the format of the state assessment. You want the students to have a chance to experience the taught skills in exactly the way they will use them in a real testing situation. If technology will be used in the spring testing, use it throughout the year to build student's confidence, skill, and knowledge with this type of platform. Highlighting, dropping, and dragging are sometimes required for students in third grade and some have never used these skills before. They shouldn't be tricked by a test format because we didn't demonstrate it and have them practice it.

- Teams, departments, and grade levels should meet frequently to review assessment results.

- Administrators should gather the data to analyze for trends. In order to design tutorial and enrichment activities, an item analysis should be conducted to study the students' areas of strength and weakness.

- Do not make this assessment data as part of student grades. This concept was hugely controversial; however, these assessments are simply are a check of the students understanding of a specific skill that was taught for a specified time period. These assessments guide immediate instruction to get all students to mastery.

- At all grade levels; share the results with the students. The students need to know this information so that they may plan for tutorial opportunities. Based on assessment results, teachers provide continuing quality instruction to either build on success or provide additional instruction.

Act

- Based on assessment results, teachers provide continuing quality instruction to either build on success or provide additional instruction.

- Teaching teams need to work together to review progress.

- Extensions must be considered as important as tutorial work and provided for both mastery and non-mastery students.

- Additional mini-assessments may be given to check for continued mastery.

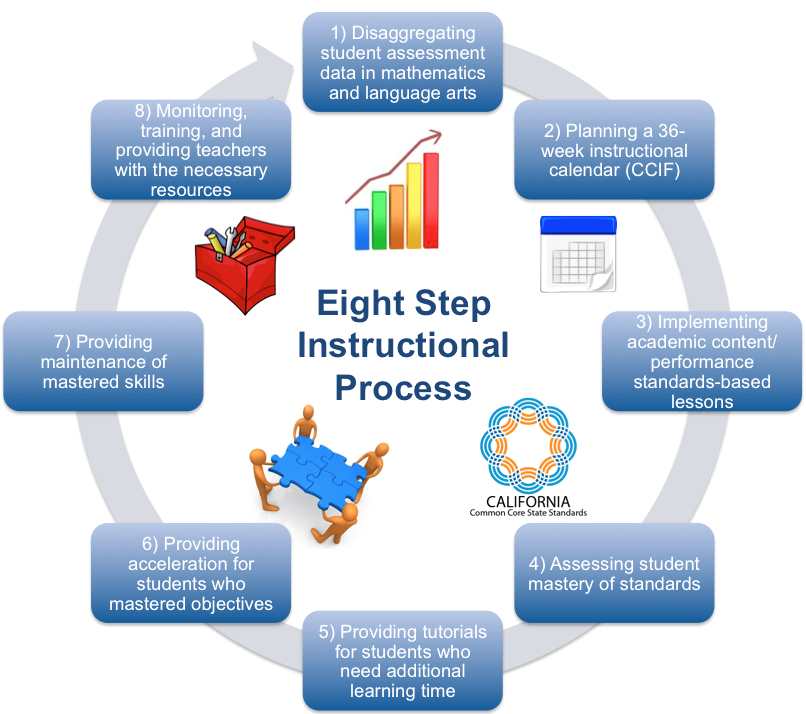

Davenport's Model

Closing the Achievement Gap: No Excuses by Patricia Davenport and Gerald Anderson is a small and powerful book; it provides a case study about Brazosport Independent School District, Texas, closed its achievement gap through deliberate planning and action. The diverse school district dramatically improved the performance and outcomes for its students by applying an 8-Step Continuous Improvement Model (CIM). This model was combined with Deming's Total Quality Management Model (P-D-C-A) illustrated above.

California adopted the Davenport model with this step-by-step approach aligned to core standards.

What's Your Focus?

A critical step in improving teaching and learning is to regularly observe and give feedback on teaching and learning. A well-established practice of classroom walkthroughs allows the principal to support implementation and professional development. A critical step in performing classroom walkthroughs is to develop a focus of inquiry that defines what individuals or teams look for in their classroom visits. Clearly defining the lens for collecting evidence is necessary for ensuring that walkthroughs will help educators answer the most important questions—those that, if answered, will help to inform what high-leverage changes the school might want to implement.

To develop a focus of inquiry, leaders may find it helpful to consider the following questions:

- What priorities and strategies outlined in the school and/or district improvement plans may benefit from new insight and progress monitoring?

- What aspects of the school and/or district vision and mission statements do we hope to see represented in the classroom? What aspects need attention?

- What do existing data reveal about student learning and opportunities for improvement? How can a focus of inquiry provide more or different information?

- What is known about root causes of low student achievement at our school? What do educational research and knowledge of best practices identify as keys to improvement?

Here are a couple of questions that could become a focus of inquiry:

- What types of questions push students to make their thinking and reasoning evident?

- What evidence suggests that students can summarize the big ideas being taught?

Excerpted from Learning Walkthrough Implementation Guide Revised edition February 2013. Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.

Start Accelerating and Stop Remediating

Learning in the Fast Lane by Suzy Pepper Rollins is one of the most important books I have read and one that I share with anyone who will listen. It's that important of a concept and that timely to what's going on in your school today…trying to figure out how to fill gaps in student's knowledge so they are successful with today's content. If you see the same children in remedial classes month after month, year after year, in RtI, and not making progress, read the teaser here, share it with your teachers, and rev your engines!

Learning in the Fast Lane by Suzy Pepper Rollins is one of the most important books I have read and one that I share with anyone who will listen. It's that important of a concept and that timely to what's going on in your school today…trying to figure out how to fill gaps in student's knowledge so they are successful with today's content. If you see the same children in remedial classes month after month, year after year, in RtI, and not making progress, read the teaser here, share it with your teachers, and rev your engines!

"The traditional remedial approaches used in countless classrooms focus on drilling isolated skills that bear little resemblance to current curriculum. Year after year, the same students are enrolled in remedial classes, and year after year, the academic gaps don't narrow. And no wonder: instead of addressing gaps in the context of new learning and helping students succeed in class today, remedial programs largely engage students in activities that connect to standards from years ago (some that aren't even tested any longer). Rather than build students' academic futures, remediation pounds away at the past. We spend significant amounts of time teaching in reverse, and then ask why students are not catching up to their peers.

Acceleration jump-starts underperforming students into learning new concepts before their classmates even begin. Rather than being stuck in the remedial slow lane, students move ahead of everyone into the fast lane of learning. Acceleration provides a fresh academic start for students every week and creates opportunities for struggling students to learn alongside their more successful peers.

We know that students learn faster and comprehend at a higher level when they have prior knowledge of a given concept. A crucial aspect of the acceleration model is putting key prior knowledge into place so that students have something to connect new information to.

Although the acceleration model does revisit basic skills, these skills are laser-selected, applied right away with the new content, and never taught in isolation. To prepare for a new concept or lesson, students in an acceleration program receive both instruction in prior knowledge and remediation of prerequisite skills that, if missing, may create barriers to the learning process. This strategic approach of preparing for the future while plugging a few critical holes from the past yields strong results."

Read more at www.ascd.org/cache/publications/books/114026/chapters/Acceleration@_Jump-Starting_Students_Who_Are_Behind.aspx

Give Students a REAL Voice in School Improvement

I admit that I am always looking to find better and more meaningful ways to include our students in more school improvement efforts more authentically. Like you, I used surveys and asked questions that I thought would get me to an answer. In reality, I was framing the surveys and questions around what I thought would be meaningful, not what the young people thought. Meaningful student involvement can transform your school by engaging student voices in student/adult partnerships that foster high levels of engagement and achievement. And we know that when students are engaged and connected, they learn more deeply and care more about their school, their education, and their world.

Meaningful Student Involvement is a model for school improvement that strengthens the commitment of students to education, community and democracy. Meaningful Student Involvement is a process of engaging students as partners in every facet of school change for the purpose of strengthening their commitment to education, community, and democracy.

The Frameworks for Meaningful Student Involvement https://soundout.org/resources/meaningful-student-involvement/ are different tools designed to help schools for on taking action with students as partners to transform schools. They do not tell you what to do; they do serve as guiding lights for change. The 12 Frameworks promote student engagement by securing roles for students in every aspect of the educational system and recognizes the unique knowledge, experience and perspective of each individual student. Adam Fletcher authors and supports SoundOut.org https://soundout.org/series-on-meaningful-student-involvement/. It is an interactive site loaded with tips and tools on getting and keeping students involved and engaged with improving their schools by improving relationships with adults and by improving ownership of their learning. Wow! Check it out.

Resources and Refrences

Baldanza, Marcia. "Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment." Professional Practices . Alexandria, VA: Just ASK Publications, May 2016.

www.justaskpublications.com/just-ask-resource-center/e-newsletters/professionalpractices/curriculum-instruction-and-assessment-2/

_____________. "School Improvement… What Matters Most?" Professional Practices . January 2018.

www.justaskpublications.com/just-ask-resource-center/e-newsletters/professionalpractices/school-improvement-what-matters-most/

Brookhart, Susan. How to Give Effective Feedback to Your Students . Alexandria, VA: ACSD, 2008.

Byrk, Anthony. "Organizing Schools for Improvement." Kappan , April 2010.

Bryk, Anthony and Barbara Schnieder. Trust in Schools: A Core Resource for Improvement . New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 2002.

Boudett, Katherine, Elizabeth City, and Richard Murnane. Data Wise, Revised and Expanded Edition: A Step-by-Step Guide to Using Assessment Results to Improve Teaching and Learning . Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2013.

Davenport, Patricia and Gerald Anderson. Closing the Achievement Gap: No Excuses . Houston, TX: APQC, 2002.

Fullan, Michael. Leadership and Sustainability: Systems Thinkers in Action . Thousand Oaks, CA and Canada: Corwin Press and The Ontario Principals' Center, 2005.

Leithwood, Kenneth, Karen Seashore Louis, Stephen Anderson and Kyla Wahlstrom. Learning from Leadership . "Review of Research How Leadership Influences Student Learning" University of Minnesota Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement, 2004.

www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/How-Leadership-Influences-Student-Learning.pdf

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary. "Learning Walkthrough Implementation Guide." Malden, MA, 2013.

www.mass.gov/edu/docs/ese/accountability/dart/walkthrough/implementation-guide.pdf

Murphy, Joseph. Professional Standards for Educational Leaders: The Empirical, Moral, Experiential Foundations . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2017.

Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (PSEL). National Policy Board for Educational Administration. Reston, VA, 2015.

www.ccsso.org/Documents/2015/ProfessionalStandardsforEducationalLeaders2015forNPBEAFINAL.pdf.

Rollins, Suzy Pepper. Learning in the Fast Lane . Alexandria, VA: ASCD. 2014.

Rutherford, Paula, et al. Creating a Culture for Learning: Focus on PLCs and More. Alexandria, VA: Just ASK Publications. 2011.

Schneider, Nancy. "As Many Ways To Improve Schools as There Are Students." Northwest Matters: Blog of Education Northwest . February, 2015.

Access at https://educationnorthwest.org/northwest-matters/many-ways-improve-schools-there-are-students.

State Efforts to Strengthen School Leadership. Council of Chief State School Officers. September 2017.

www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/State-Efforts-Strengthen-School-Leadership-CCSSO-Action-Groups-PSA-2017.pdf.

Stronge, James and Pamela Tucker. Handbook on Teacher Evaluation: Assessing and Improving Performance. Larchmont, NY: Eye On Education. 2003.

Wiggins, Grant. "Feedback: How Learning Occurs." The American Association for Higher Education Bulletin . November, 1997.

Permission is granted for reprinting and distribution of this newsletter for non-commercial use only.

Please include the following citation on all copies:

Baldanza, Marcia. "School Improvement… What Matters Most? Part II" Professional Practices . February 2018. Reproduced with permission of Just ASK Publications & Professional Development. © 2018 All rights reserved.

torresbobloventold1965.blogspot.com

Source: https://justaskpublications.com/just-ask-resource-center/e-newsletters/professionalpractices/school-improvement-what-matters-most-part-2/

0 Response to "Cycle of Continuous Improvement Ccsso 2017"

Post a Comment